Humans have wanted to talk with the animals for centuries. From early mythology to the fictional children’s books featuring Doctor Doolittle in the early 20th century, either humans or animals (or both) have been imagined with “special powers” to understand one another’s language.

Humans have wanted to talk with the animals for centuries. From early mythology to the fictional children’s books featuring Doctor Doolittle in the early 20th century, either humans or animals (or both) have been imagined with “special powers” to understand one another’s language.

However, it wasn’t until the mid 20th century that someone (Allen and Beatrix Gardner in 1967) had the brilliant idea of trying to teach “sign language” to a chimpanzee (Washoe). This made sense as chimpanzees (and other great apes) are the closest genetic species to humans, they use gestural communication with each other, and earlier attempts to get them to “speak” (such as Viki, a chimpanzee) failed due to inherent physiological limitations.

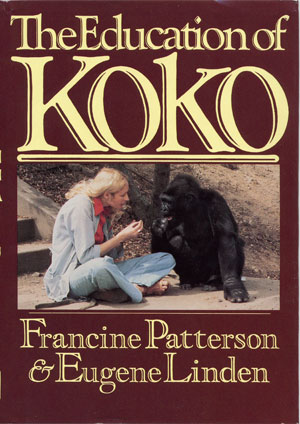

The success of PROJECT WASHOE prompted Dr. Francine “Penny” Patterson to attempt a similar study with gorillas, in 1972, which became known as PROJECT KOKO, and later evolved into The Gorilla Foundation.

There are many reasons to attempt to communicate with other species — especially our fellow great apes — and benefits for all concerned:

1) We get to learn more about their thoughts and feelings, and because of our similarities, this helps us to understand more about our own cognitive development as a species.

2) It enables us to take better care of them in captivity (zoos and sanctuaries), as they can tell us what they want and need, and we can optimize what we give them to maximize their comfort or joy

3) It enriches both their lives and ours in captivity, enabling them to develop richer, more interactive relationships with their caregivers. This also enriches the lives of their caregivers, converting what could be come a routine job into an evolving learning experience and in some cases a friendship.

4) It increases interspecies empathy, and can thus have a major impact on conservation. Imagine zoo visitors not only being able to “watch” gorillas in their enclosures, but also being able to understand their conversations, with each other, their caregivers, or even the visitors themselves (if moderated by caregiver hosts).

5) With increased empathy for other species comes the strong inclination to save them from unnecessary (man-made) extinction in the wild, and increased responsibility for our shared environment, and by protecting their environments we also protect our own.

The Gorilla Foundation is best known for Project Koko, the first and only interspecies communication study ever performed with gorillas. It is also the longest running interspecies communication study in history (46 years). It involved 1 female and 2 male Western Lowland Gorillas: Koko, Michael and Ndume, and began in 1972, when Koko was one year old.

Koko

Koko was born in the San Francisco Zoo in 1971 and spent the first six months of her life in the nursery of the children’s zoo behind a glass window where the public could see her and where Penny Patterson, then a Stanford graduate student, met her. From age six months to one year Koko was critically ill and moved to a trailer on zoo property. Penny began working with Koko when she recovered her health, and requested permission from the zoo to continue working with her as part of her Ph.D. research in psychology at Stanford University. The zoo agreed as long as Penny agreed to make at least a “4-year” commitment.

Koko was born in the San Francisco Zoo in 1971 and spent the first six months of her life in the nursery of the children’s zoo behind a glass window where the public could see her and where Penny Patterson, then a Stanford graduate student, met her. From age six months to one year Koko was critically ill and moved to a trailer on zoo property. Penny began working with Koko when she recovered her health, and requested permission from the zoo to continue working with her as part of her Ph.D. research in psychology at Stanford University. The zoo agreed as long as Penny agreed to make at least a “4-year” commitment.

In 1974 Koko and her trailer were moved to Stanford University where Penny and Dr. Ron Cohn continued to work with her, and they have been together ever since. Michael, a male gorilla, joined Koko in 1976, and in 1979 the whole group moved to Woodside, CA where Ndume, a second male gorilla joined the group in 1991.

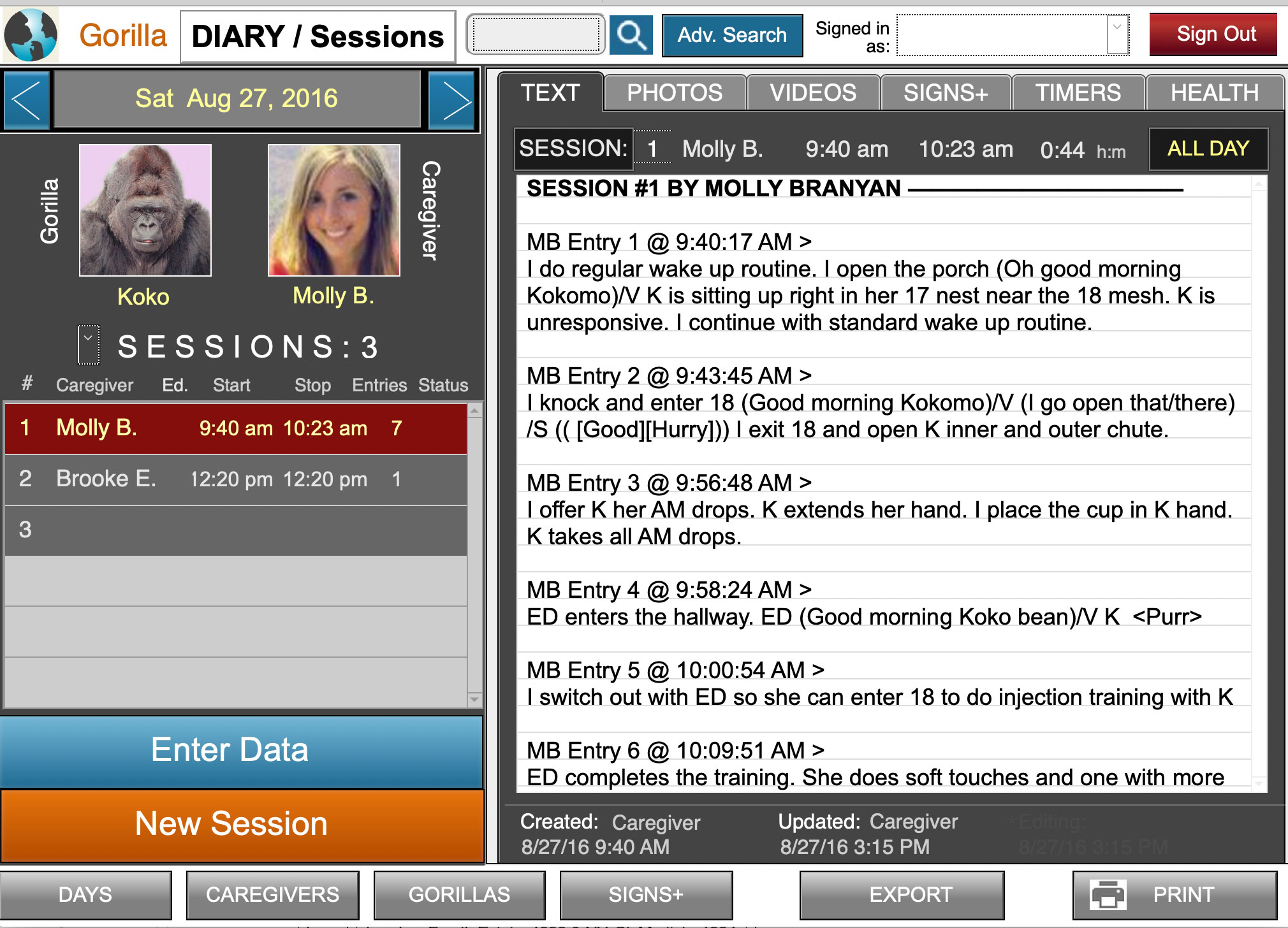

In the years since 1971, Penny (Dr. Patterson) has spent her life caring for Koko and the two male gorillas (Michael and Ndume) — with a very dedicated rotating team — and has established highly empathic relationships with them that may be difficult to replicate by others due to the commitment required. A successful program such as this requires using language during daily documented interactions, as well as the ability to “listen” to the gorillas and discern their meanings. Few people have the patience, stamina, and sensitivity to achieve this.

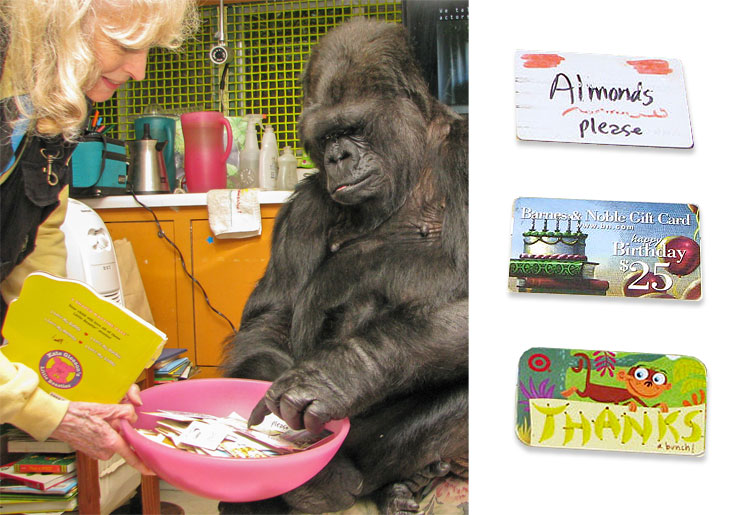

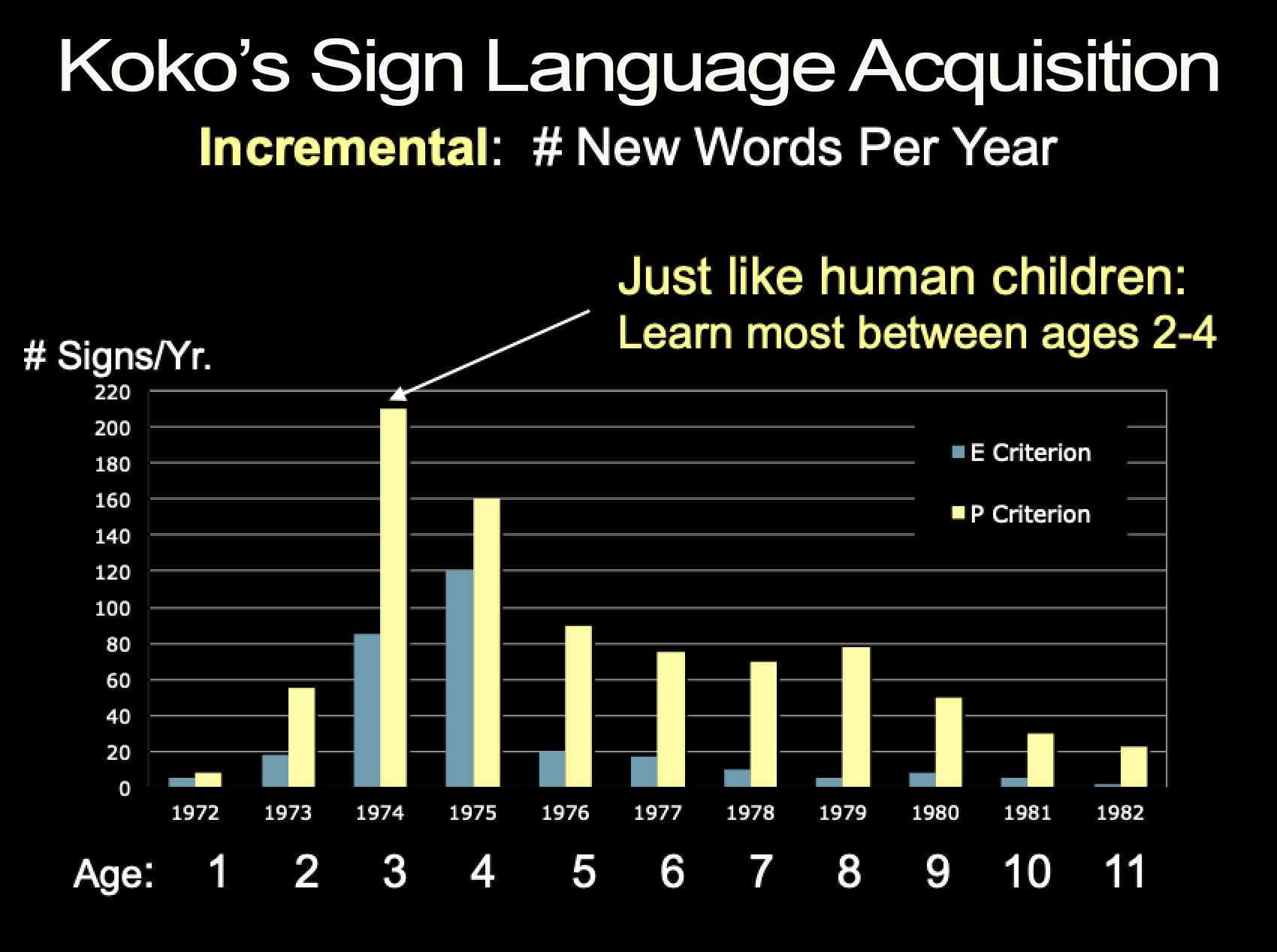

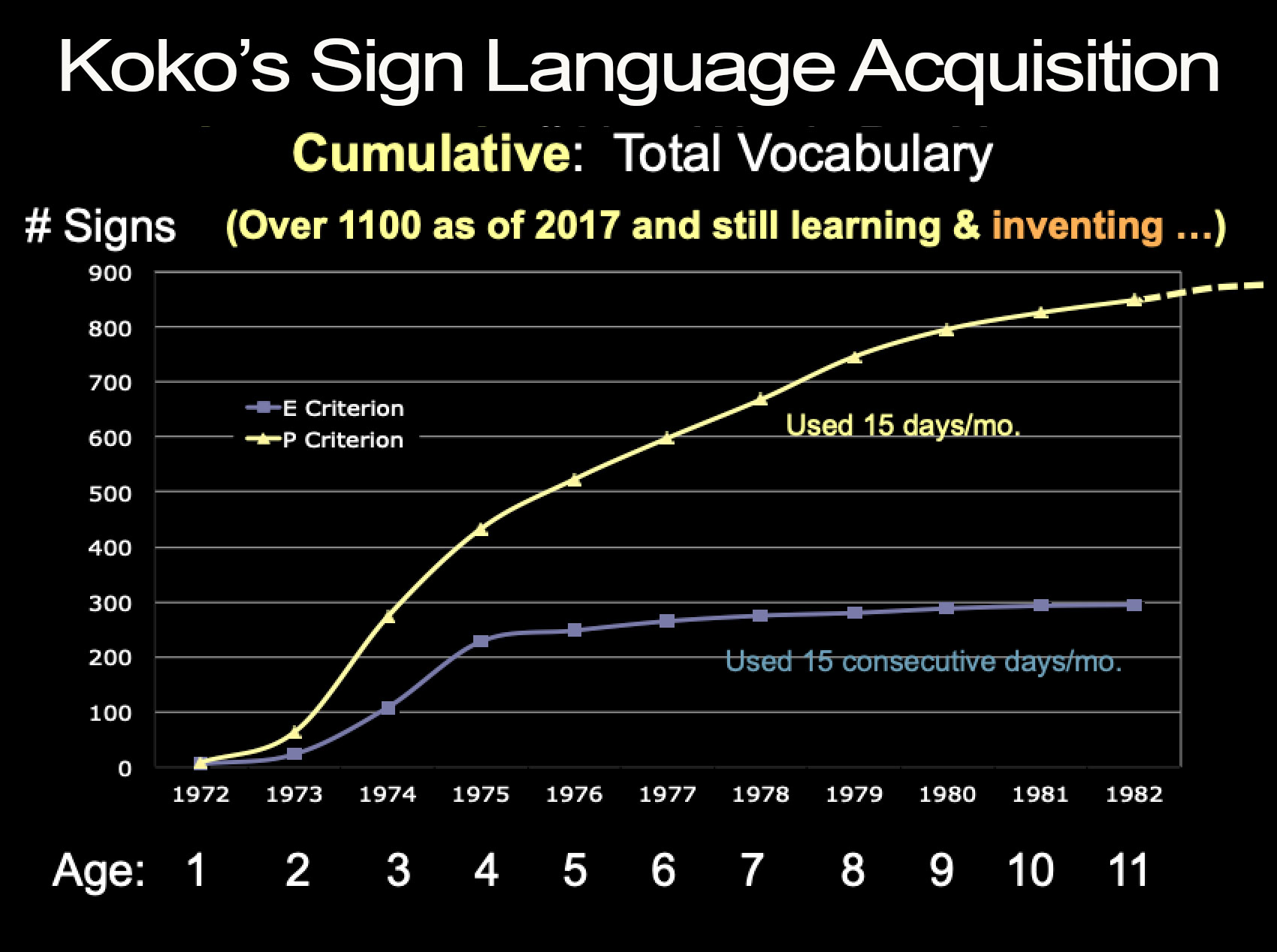

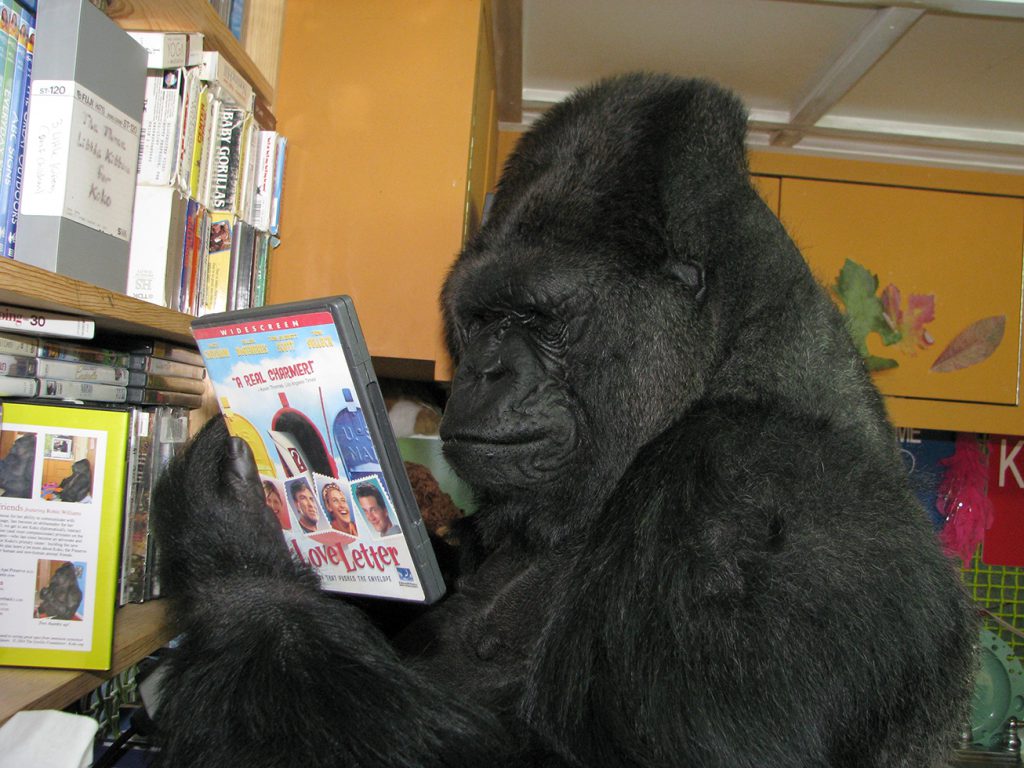

With Penny’s help, Koko has learned to use over 1,000 signs and seems to understand approximately 2,000 spoken English words. Further, Koko understood these signs sufficiently well to adapt them or combine them to express new meanings that she wants to convey. Importantly, Koko began learning to sign from Penny in just a few short weeks. Penny believes this is because signing is “wired in” to the great apes (over a hundred natural, untaught, gestures have been observed in zoos around the world. This bodes well for any gorilla in captivity who could benefit from a closer relationship with his/her caregiver, which is made possible through two-way communication.

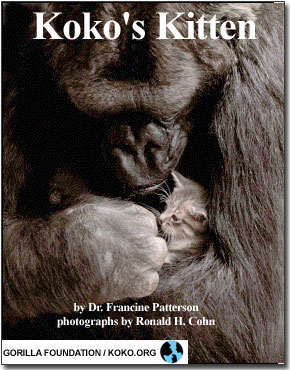

Sadly, Koko passed away in her sleep on June 19, 2018, at the age of 46 (2 weeks before her 47th birthday on July 4th). She gave the world a whole new paradigm for gorillas (from King Kong to Koko’s Kitten), volumes of multimedia data on interspecies communication and care to build upon, and inspired millions of people around the world to care about their fellow great apes, and our shared environment. Her legacy will live on through all the other gorillas and children she has affected — and through the continued work of The Gorilla Foundation.

Michael

Gorilla Michael, who grew up with Koko from age 3, was a “bushmeat orphan” and apparently witnessed his mother killed by poachers before being rescued and sent to a European zoo. He too learned hundreds of signs of signs (over 500 by the time he was an adult), and developed other communication-related skills, such as painting beautiful representational and abstract works of art.

Gorilla Michael, who grew up with Koko from age 3, was a “bushmeat orphan” and apparently witnessed his mother killed by poachers before being rescued and sent to a European zoo. He too learned hundreds of signs of signs (over 500 by the time he was an adult), and developed other communication-related skills, such as painting beautiful representational and abstract works of art.

Michael passed away in 2000 at the age of 27, from Cardiomyopathy (an enlarging of the heart muscle) a disease which is fairly common in captive male gorillas, and is possibly stress-related.

The fact that Michael was able to learn sign language as easily as Koko points to an important observation that is supported by other research as well as our own: Koko is not unique. There is nothing special about Koko or Michael. They were selected from two completely different environments not because they had a predisposition for communication, but because they both needed a loving home. Sign language appears to be a natural form of communication for gorillas (they have been observed using over a hundred natural (untaught by us) gestures in captivity), and so why not teach them a “common” form of sign language so that we can understand each other better? And the fact that Michael was able to remember his mother being killed by poachers (possibly the only first-hand account of the “bushmeat” trade by a survivor, suggests that orphan gorillas living in sanctuaries might find a shared sign language a useful therapy for dealing with PTSD.

Ndume

Finally, Ndume came to live with Koko and Michael in 1991 at age 10, from the Cincinnati Zoo, and lived at the Gorilla Foundation’s Woodside Sanctuary for 27 years, as Koko’s close companion (she selected him via something like “video dating”). Ndume came with some of his own natural gestures, and learned more from both Koko and caregivers. However, at the request of the zoo who “lent” Ndume to us, he was never formally taught sign language. After Koko passed away, the zoo decided to exercise their right (in our agreement) of returning him to the zoo. At the time of this writing, he has been there for only a few days, accompanied by two of our caregivers, and we are all hoping he will adapt to his new (and very different for him) environment. However, it is a stressful time for everyone, as while gorillas are the largest and strongest great ape species, they are also the most emotionally fragile.

Finally, Ndume came to live with Koko and Michael in 1991 at age 10, from the Cincinnati Zoo, and lived at the Gorilla Foundation’s Woodside Sanctuary for 27 years, as Koko’s close companion (she selected him via something like “video dating”). Ndume came with some of his own natural gestures, and learned more from both Koko and caregivers. However, at the request of the zoo who “lent” Ndume to us, he was never formally taught sign language. After Koko passed away, the zoo decided to exercise their right (in our agreement) of returning him to the zoo. At the time of this writing, he has been there for only a few days, accompanied by two of our caregivers, and we are all hoping he will adapt to his new (and very different for him) environment. However, it is a stressful time for everyone, as while gorillas are the largest and strongest great ape species, they are also the most emotionally fragile.

_________________________________

The following 3 video clips provide highlights of interspecies communication recorded with gorillas Koko, Michael and Ndume. Note, that over 2000 hours of videos have been collected during Project Koko, but only a fraction have been studied sufficiently to share with the public. There is much to do; and one of our Top Initiatives, the Koko Archive, is intended to complete the “Koko Digital Archive” with the help of both the general public and interested researchers.

The Gorilla Foundation (Koko.org) has pioneered Interspecies Communication (IC) with gorillas for over 4 decades. Through an integrated process of research and gorilla care, we have worked with and cared for 3 western lowland gorillas: Koko, Michael and Ndume.

The Gorilla Foundation (Koko.org) has pioneered Interspecies Communication (IC) with gorillas for over 4 decades. Through an integrated process of research and gorilla care, we have worked with and cared for 3 western lowland gorillas: Koko, Michael and Ndume.

Humans have wanted to talk with the animals for centuries. From early mythology to the fictional children’s books featuring Doctor Doolittle in the early 20th century, either humans or animals (or both) have been imagined with “special powers” to understand one another’s language.

Humans have wanted to talk with the animals for centuries. From early mythology to the fictional children’s books featuring Doctor Doolittle in the early 20th century, either humans or animals (or both) have been imagined with “special powers” to understand one another’s language.

Koko was born in the San Francisco Zoo in 1971 and spent the first six months of her life in the nursery of the children’s zoo behind a glass window where the public could see her and where Penny Patterson, then a Stanford graduate student, met her. From age six months to one year Koko was critically ill and moved to a trailer on zoo property. Penny began working with Koko when she recovered her health, and requested permission from the zoo to continue working with her as part of her Ph.D. research in psychology at Stanford University. The zoo agreed as long as Penny agreed to make at least a “4-year” commitment.

Koko was born in the San Francisco Zoo in 1971 and spent the first six months of her life in the nursery of the children’s zoo behind a glass window where the public could see her and where Penny Patterson, then a Stanford graduate student, met her. From age six months to one year Koko was critically ill and moved to a trailer on zoo property. Penny began working with Koko when she recovered her health, and requested permission from the zoo to continue working with her as part of her Ph.D. research in psychology at Stanford University. The zoo agreed as long as Penny agreed to make at least a “4-year” commitment. Gorilla Michael, who grew up with Koko from age 3, was a “bushmeat orphan” and apparently witnessed his mother killed by poachers before being rescued and sent to a European zoo. He too learned hundreds of signs of signs (over 500 by the time he was an adult), and developed other communication-related skills, such as painting beautiful representational and abstract works of art.

Gorilla Michael, who grew up with Koko from age 3, was a “bushmeat orphan” and apparently witnessed his mother killed by poachers before being rescued and sent to a European zoo. He too learned hundreds of signs of signs (over 500 by the time he was an adult), and developed other communication-related skills, such as painting beautiful representational and abstract works of art. Finally, Ndume came to live with Koko and Michael in 1991 at age 10, from the Cincinnati Zoo, and lived at the Gorilla Foundation’s Woodside Sanctuary for 27 years, as Koko’s close companion (she selected him via something like “video dating”). Ndume came with some of his own natural gestures, and learned more from both Koko and caregivers. However, at the request of the zoo who “lent” Ndume to us, he was never formally taught sign language. After Koko passed away, the zoo decided to exercise their right (in our agreement) of returning him to the zoo. At the time of this writing, he has been there for only a few days, accompanied by two of our caregivers, and we are all hoping he will adapt to his new (and very different for him) environment. However, it is a stressful time for everyone, as while gorillas are the largest and strongest great ape species, they are also the most emotionally fragile.

Finally, Ndume came to live with Koko and Michael in 1991 at age 10, from the Cincinnati Zoo, and lived at the Gorilla Foundation’s Woodside Sanctuary for 27 years, as Koko’s close companion (she selected him via something like “video dating”). Ndume came with some of his own natural gestures, and learned more from both Koko and caregivers. However, at the request of the zoo who “lent” Ndume to us, he was never formally taught sign language. After Koko passed away, the zoo decided to exercise their right (in our agreement) of returning him to the zoo. At the time of this writing, he has been there for only a few days, accompanied by two of our caregivers, and we are all hoping he will adapt to his new (and very different for him) environment. However, it is a stressful time for everyone, as while gorillas are the largest and strongest great ape species, they are also the most emotionally fragile.